“Flipping” the Narrative of America’s First Ladies

Why historic site leaders want stories amplifying first ladies standing on their own.

Deep in the Hudson Valley region of New York, not far from the edge of Val-Kill Pond, sits a stone cottage of the same name against a backdrop of lush forestry where curiosity-seekers from around the globe come to visit.

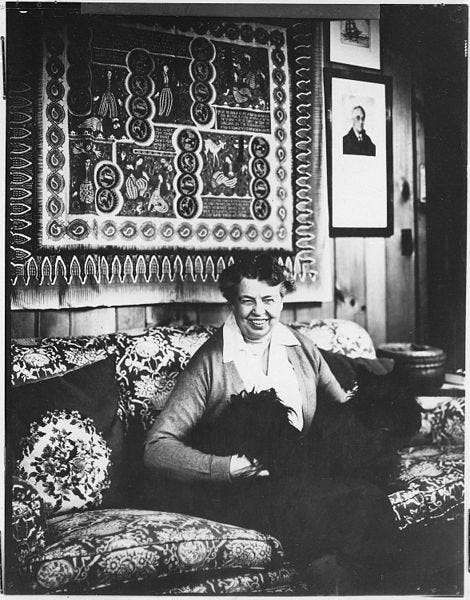

This is Val-Kill cottage — the first historic site designated in honor of an American first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt. Situated on the outskirts of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum in Hyde Park, the cottage, in some ways, symbolizes the stature of first ladies and their evolving influence in their counterparts’ political spheres. The cottage is located on the far end of the estate, about two miles from Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Springwood Mansion and adjacent presidential library. It stands on its own.

Similarly, that was one theme echoed this week when some leaders of historic presidential sites across the country converged a…